by Terry Meyers, Chancellor Professor of English, Emeritus

In recent months I’ve turned my research on slavery and race at William & Mary towards Jim Crow segregation. As a step towards that I’ve been skimming university publications from the early 20th century on into the 1970’s, indexing them for references to race (indices for The Flat Hat, Colonial Echo, and the Alumni Gazette are available at the Lemon Project Research and Resources page).

Indexing is not always a stimulating undertaking, though I’m always stumbling across interesting tidbits about W&M. And in terms of race at the College (as it was called then), I’ve found some particularly interesting items.

The first is a short account of the earliest Black people to study in any formal way under the aegis of William & Mary. We have, of course, some accounts of enslaved and free African-Americans who picked up a modicum of education informally, from simply being around students and classrooms; see for example James Hambleton Christian who ultimately self-liberated after serving in the John Tyler White House but who at W&M “through the kindness of the students … picked up a trifling amount of book learning.”

I happened across a brief paragraph in The Flat Hat:

The colored classes of Williamsburg are a part of the William and Mary extension division. They are composed of colored teachers throughout the county [likely James City County] who have had training at Hampton Normal, Petersburg Normal or some other school but have not had an opportunity to attend college. There are about twenty enrolled in the class under the instruction of the English department of the college.

The Flat Hat, November 24, 1925

And that’s all I know so far. Sallie Marchello, then Register at W&M, undertook to review all the official records of the time, but found nothing, no record of the course, no title or subject, no instructor, no class list. Given as part of the extension courses W&M then offered around the region to people not enrolled at the College, the course was likely offered off campus, perhaps at a local Black school. It certainly was offered off the books.

Given the Jim Crow values of the time, offering the course at all was unusual. It seems unlikely that the English Department would offer it without permission from the President of the College and the Board of Visitors, but any evidence of that is yet to show up. I have found, however, that at least three members of the Board around that time were progressive, at least by the standards of the era, so the course might well have been sanctioned from above. See Wikipedia for more about the three: James H. Dillard (Rector of the Board of Visitors, 1919-1941), Kate Waller Barrett, and Mary-Cook Branch Munford.

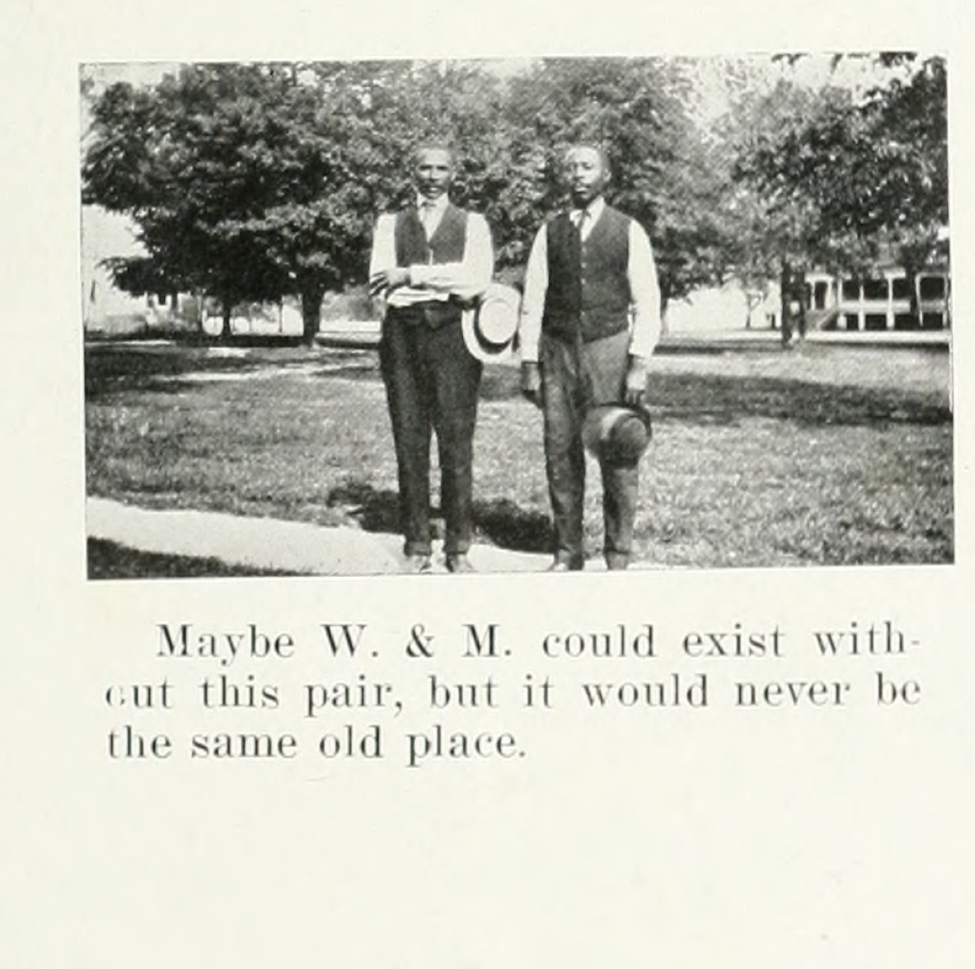

My second find is three pictures in Colonial Echo yearbooks of Black workers at W&M in 1918, 1920, and 1921. The first shows Henry Billups and another man; the caption is appreciative:

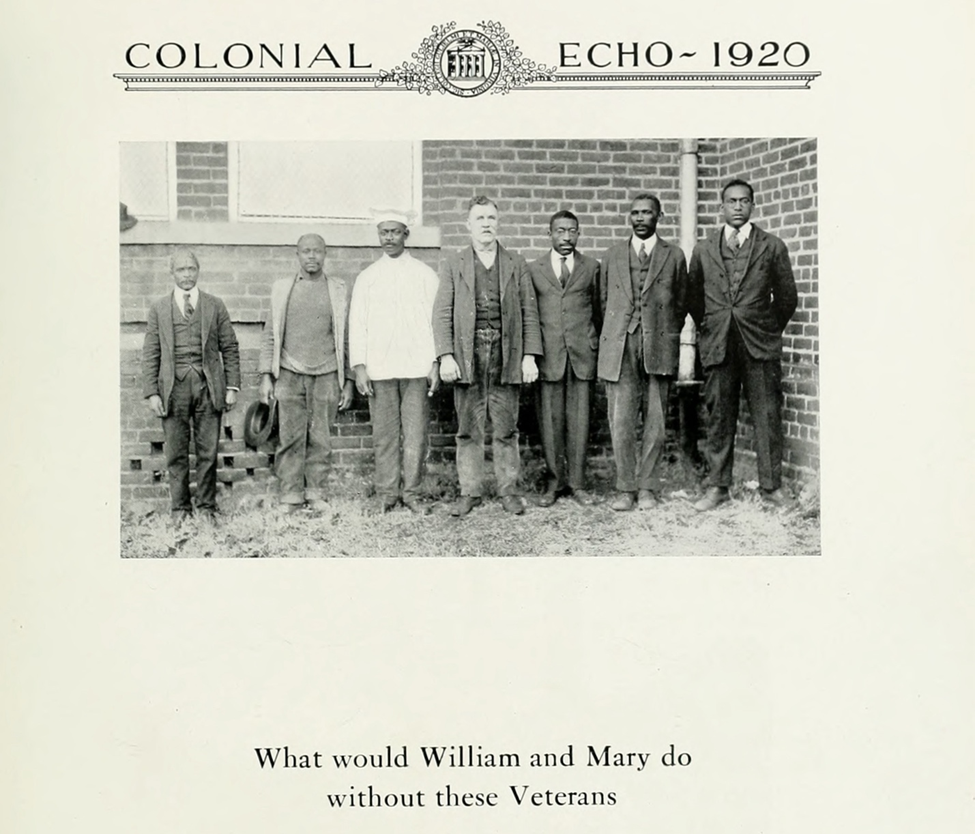

The second shows seven men, again with an appreciative caption:

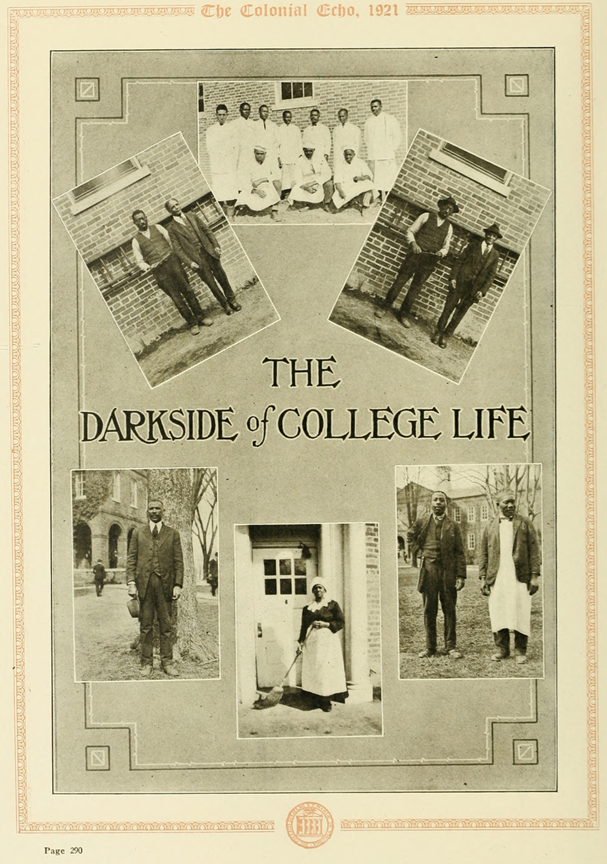

The caption under the third (below) is patronizing and even insulting, but it is at least a further and welcome acknowledgement of what over the decades and centuries has sustained the academic enterprise of students and faculty– the work of Black workers, hard, steady, and underpaid. In 1939, the President of the College raised the pay of the Black workers (not the white) in the dining room—he found it “difficult to understand” why they had stayed when they were so underpaid.

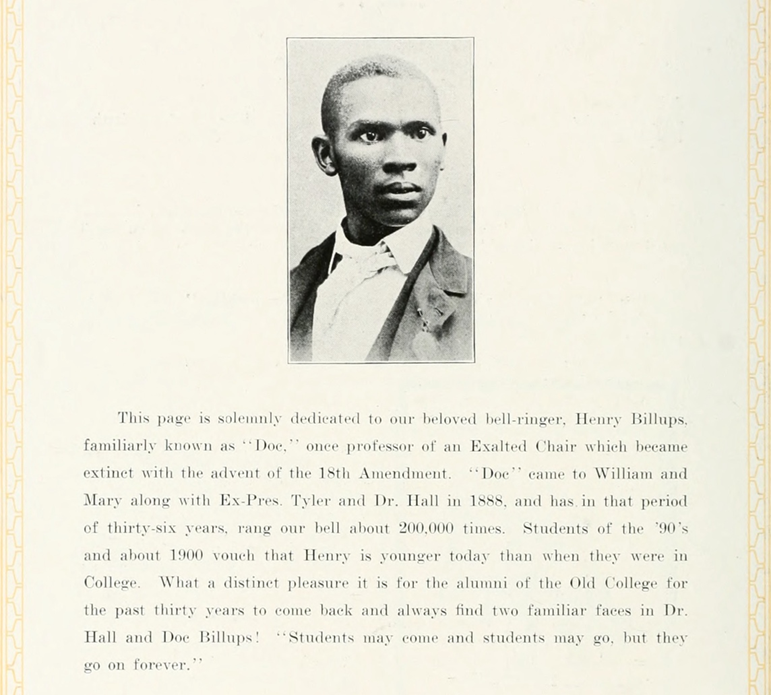

Other such acknowledgements have occurred, though rarely. Henry Billups, the Wren custodian and bell-ringer, worked at the College from 1888 to close to his death in 1955 and was much honored and appreciated. See the account by Trudier Harris at the LP site and this tribute in the 1926 Colonial Echo:

Malachi Gardiner, who worked for Benjamin Ewell through the closure of the College and its reopening in 1888 and then well into the 20th century, is featured in the March 31,1938 issue of the Alumni Gazette. Alex Goddall, a long-time custodian, features in The Flat Hat three times (March 4, 1927. May 5, 1936, and March 2, 1937), in the Alumni Gazette (March 31, 1937), and even in a Richmond News-Leader piece (December 23, 1938).

More recently, the earliest issues of The William and Mary News, edited by Eleanor Anderson, an African-American (September 12, 1972), initiated features on members of the staff including early on Arthur Hill, successor to Henry Billups (September 12, 972); three housekeeping staff in Jones Hall (Gwendolyn Bell, Cornelia Williams, and Hattie Cox); Alton Wynn, supervisor for passenger vehicle transportation; and Fred Crawford, Chef at the President’s House (December 12, 19,1972).

In 2004, Ernestine Jackson, a food services worker popular with students, was recognized by a Virginia Senate resolution. On his retirement from the Wren Building, Bernard Bowman was featured in the Virginia Gazette (July 25, 2023). And most recently, Jesse Jenkins was saluted in the October 8, 2025 issue of The Flat Hat.

None of the people in the photographs below are named; Henry Billups is the man in the photo at lower left, and I believe the man on the left of the top right photo is Malachi Gardiner; I think one of the other men may be Lisbon Gerst, who laid all the brick walkways at the College (some he laid may still be seen near Hearth). The men in the top photo likely worked in the kitchen and dining hall (and some may have been among those whose salaries were raised in 1939).

I was tempted several decades ago into the then-taboo subject of W&M, slavery, and segregation though an encounter with a nefarious figure, Thomas Roderick Dew, W&M President, 1835-1846. I assumed he epitomized three centuries of thinking about African-Americans here: he was one of the most fervent and influential pro-slavery ideologues in the ante-bellum South. And at the height of Jim Crow, William & Mary honored his life and work in reinterring him in the Chapel crypt in 1939.

I assumed all of W&M’s history vis-a-vis race was ugly—and it surely is to a large extent. But what I’ve discovered is that it’s complicated. There are bright spots in our dimness. Unlike our fellow colleges in colonial times, W&M was touched by the European Enlightenment and was intellectually and in its teachings so emancipationist that most of its graduates were said in the early 19th century to be abolitionists. Jefferson, for all his hypocrisies and contradictions, deepened his antipathy to slavery here as a student, and later encouraged W&M’s curricular skepticism about it. One of our enslaved, Winkfield, Superintendent of the Great Hall, was quoted as repudiating white supremacy. And with our affiliation to the Bray School, W&M was the first college or university in America to concern itself with Black education (limitations and qualifications apply).

And that complexity manifests itself in my indexing of Jim Crow-era publications at the university—lots of darkness, but spots of relative light, like the 1925 course offered to local Black teachers and like the intermittent recognition of the Black workers underpinning the life, studies, and teaching of other workers, students, and faculty.

I would guess that later users of my indices will see much the same.

Note: The contributions shared here represent the author’s views and historical interpretation; for further questions, contact the writer.