By Omiyẹmi (Artisia) Green, Professor of Theatre and Africana Studies, University Professor of Teaching Excellence, Provost Faculty Fellow

On W&M’s 333rd Charter Day, to say that my heart swelled as I watched community members make their way to the Hearth: Memorial to the Enslaved would be an understatement. Still, it is the closest language I have for the immense pride and quiet fulfillment I felt witnessing people arrive bundled and layered against the cold (I had on three layers myself), carrying flowers, instruments, and hearts full of tribute for those enslaved by the Alma Mater of the Nation.

Over the past academic year, I have been intentionally building an archival box of my work and achievements at William & Mary, which I plan to submit to Special Collections upon the completion of my tenure. This impulse emerged while editing my Tack Lecture on “A History of African American Theatre and Black Theater at William & Mary Theatre.” Having spent so much time in Swem Library tracking documents and conducting oral history interviews, I became acutely aware of how the presence and absence of material shapes institutional records and future perspectives. People will remember, say, and write what they will. I wanted, however, to exercise a measure of agency over my own record. Thus, my archival box will stand as my voice.

It is in that spirit that I offer this reflection.

The Humble Beginnings (2024)

What is now the “Charter Day Ancestral Remembrance Tribute” began humbly and sacredly in 2024, on February 9th at 6 a.m., with just me and my Ibeji, Iya Ifasola Osunponmile, offering libation and prayers. The ceremony was born from my own pain and from a growing awareness of what felt like a concerted period of pressure on Black women in higher education. We were resigning due to bullying, becoming ill or dying under the weight of stress, navigating toxic work environments and racial weathering, and, in some cases, confronting stories of self-harm.

My Ibeji, another Black woman not in the academy but deeply attuned to my realities, stood with me in what was an intentional intervention, first for myself, and then for others navigating similar conditions across higher education.

It felt right to bring this act of care to a public ancestral altar, and the Hearth offered that possibility. Holding our gathering on Charter Day, while inviting peers at other institutions to gather simultaneously wherever they felt led, resonated deeply. It braided past and present labor into a shared act of remembrance and created space for collective grief, reflection, and guidance.

Why the Hearth on Charter Day Matters

There was another reason gathering at the Hearth on February 6th mattered. As far as I knew, there were no signature Charter Day proceedings at William & Mary that centered on the humanity and contributions of those it once enslaved. I am not referring to the reading of a Land Acknowledgement or the Statement on Slavery and Its Legacies at another event, but to a dedicated and exclusive program. As an alumna and a current member of the faculty, that absence made this intervention all the more necessary.

William & Mary is known for many things, tradition among them. And traditions are not only inherited; they are made. As Alice Walker reminds us, “…we are the ones we’ve been waiting for.” So, with the support of another culture bearer, I began an offering, one that is now entering institutional memory and, over time, I hope, will become part of how the university remembers itself.

Building on a Legacy

I came to this work of remembrance deeply informed by the cultural stewardship of William & Mary faculty, specifically Dr. Joanne M. Braxton. Her scholarship and vision through the Middle Passage Project, along with her leadership on the board of the Middle Passage Ceremonies and Port Markers Project, Inc., demonstrated how remembrance can be both scholarly and sacred, public and personal. The Charter Day Ancestral Remembrance Tribute, which stands on this continuum of care, labor, and ethical attention, is part of a lineage of stewardship in honoring those who came before while creating space for future generations to remember, reflect, and act.

Institutional Support and Recognition (2025–2026)

In 2025, leadership within the Forum (formerly the Black Faculty and Staff Forum) helped expand the initiative into a ceremony of collective remembrance and pressed the idea of institutionalizing the tribute at the university level. The executive board believed that situating a collective offering at the Hearth, the university’s most visible and intentional site honoring the lives and labor of the enslaved, ensured that Charter Day celebrations would be grounded in historical truth and ethical reflection.

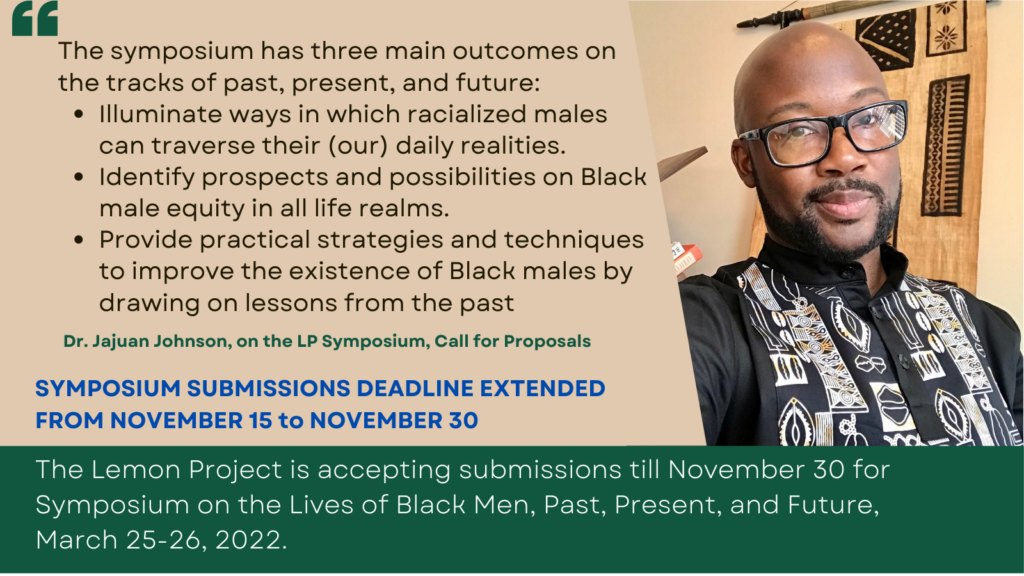

This year, the Charter Day Ancestral Remembrance Tribute gained further momentum and institutional support through sponsorship from The Lemon Project: A Journey of Reconciliation, under the leadership of Interim Robert Francis Engs Director Dr. Jajuan Johnson and Associate Director Dr. Sarah Thomas, with administrative coordination from Andrea Harris, Senior Associate Director of University Events in University Marketing.

Acknowledging Labor and Stewardship

Making visible the labor, seen and unseen, that sustained this ceremony is central to the work. The grounds for this year’s ceremony were made safe through the care of Jeffrey Harris, Mike Fowler, Dennis Doyle, Kareem Harding, Harrison Cherry, Trashawne Swittenberg, and Kyle Jenkins in Grounds & Gardens, who de-iced and salted the area in advance. Kristi Dodson, also in Grounds & Gardens, ensured I could retrieve my ceremonial flowers from my office and return to the Hearth in time for the ceremony to begin. Student employees in Facilities Management tended to the Hearth’s flame with intention.

Around the fire, stories of resistance were shared, including one powerful account from Dr. Hannah Rosen, program director of American Studies. Alumni serving on W&M leadership boards made space in already full Charter Day schedules to attend, and the College of Arts & Sciences Dean, Dr. Suzanne Raitt, also attended. One community member, en route to Murfreesboro, North Carolina, for the unveiling of the highway historical marker honoring Hannah Crafts (the pen name of Hannah Bond, an enslaved woman who escaped and authored The Bondwoman’s Narrative), participated in both the 7 a.m. and 1 p.m. ceremonies before continuing their journey.

With the support of Monique Williams, Ed.S., Director of the Student Center for Inclusive Excellence, and Kristina James, Senior Event & Scheduling Specialist in Student Unions & Engagement, student leaders were involved as stewards of memory and placemaking. They, along with faculty in Theatre & Performance (Dr. Sarah Ashford Hart), English (Professor Hermine Pinson), Music (Professor Victor Haskins), History, and the programs of Africana Studies (Dr. Iyabo Osiapem), American Studies, and Gender, Sexuality & Women’s Studies, secured flowers and/or composed tributes and performances.

In 2025, the following Registered Student Organizations helped shape the ceremony’s early collective form: Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., Kappa Pi Chapter; Kappa Alpha Psi Fraternity, Inc., Xi Theta Chapter; Minorities Against Climate Change; Students of Caribbean Ancestry; Student Assembly’s Committee for the Contextualization of Campus Landmarks & Iconography; and Emerald Elite Stomp n’ Shake. This foundation was carried forward and broadened in 2026, with continued participation from some of those same groups alongside new voices, including the Black Law Student Association, Black Poets Society, Black Student Organization, and the W&M Chapter of the NAACP.

Reflections and Hopes

Together, faculty, staff, students, alumni, and community members—across time—continue to build on the strength, contributions, and resilience of those enslaved by William & Mary, and we commit ourselves to honoring their humanity and legacy in our work. I close with three hopes for the future:

- I hope that the Charter Day Ancestral Remembrance Tribute, in its growth and continuity, will stand as a living testament to the importance of labor that is both critical and often forgotten.

- I hope that this collective act of cultural stewardship will endure not only as a reflection on the past but also as a signature placemaking event for future generations, “for all time coming.”

- And lastly, I hope that it remains an event that reinforces our university’s value of belonging while reinvigorating us for the ongoing relational work ahead.