By Alexis Beck, William & Mary Sharpe Scholar, with Caroline Watson, Lemon Project Graduate Assistant

Reflecting on my time at The Lemon Project, I can’t help but be amazed at how fun and interesting it has been. The project itself is dedicated to uncovering and preserving lesser-known pieces of history, particularly those concerning the African American communities at William & Mary and in Williamsburg broadly. However, a singular photo captivated my attention and enhanced my experience as a first-year Sharpe Scholar.

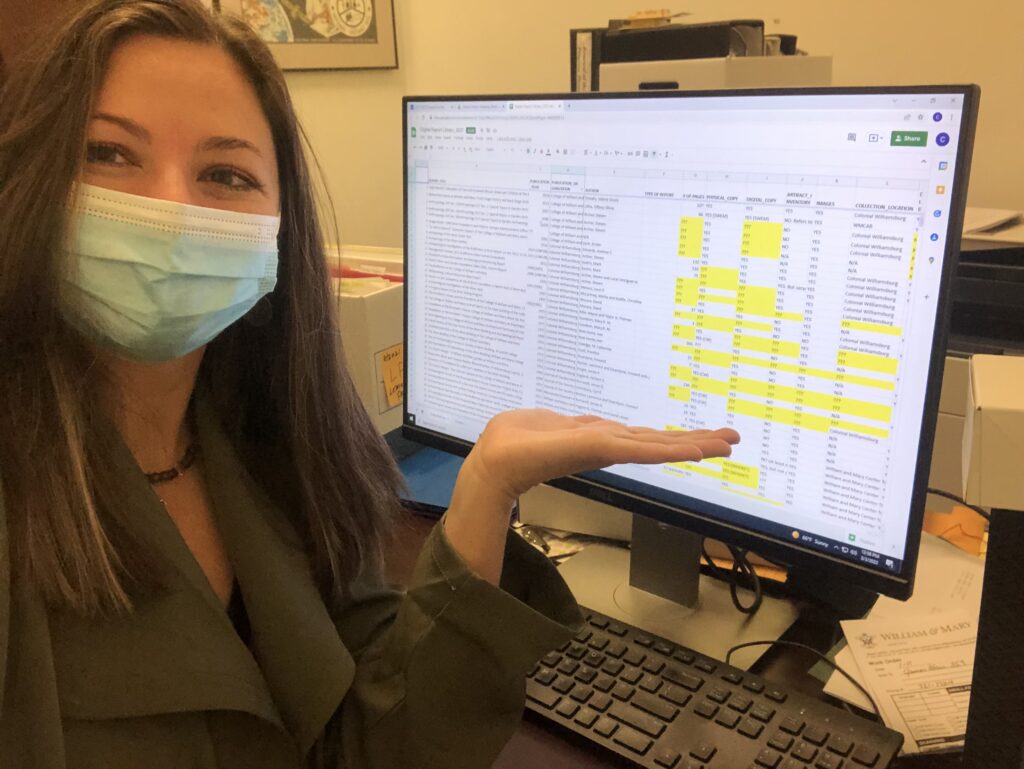

During my involvement with The Lemon Project, I worked with Ph.D. student Caroline Watson to learn more about William & Mary’s archaeology documentary archive. During this work, Caroline found an intriguing photo in the Anthropology attic archive. When she had the time, she eagerly showed me this photo, which in physical form lacked proper documentation. There was no description or timestamp. It appeared to be from the early 1930s, possibly even the 1940s, based on the material context clues, like the style of archeology, the tools, the wooden shed, and the Oldsmobile-style car in the background. This photo became a captivating mystery project that Caroline and I embarked on. With further research, we eventually unraveled the mystery behind the photo. We learned that the photo was already well-documented by Colonial Williamsburg. It turned out to be a snapshot of the Governor’s Palace from 1930, featuring a group of unknown Black archaeologists who had worked on the earlier restoration of Colonial Williamsburg. Colonial Williamsburg’s Meredith Poole provides context on the photo here.

This photo piqued my interest because it demonstrated the major contributions made by Black archaeologists at a period when their presence in the field was frequently overlooked, marginalized, or outright erased. Indeed, this snapshot expands on our understanding of the physical and social aspects of archaeological operations in early 20th-century Williamsburg. Yet, some questions haunted us during this process of learning more about the photo. Questions like, “Who are the black men archaeologists depicted here?” and “Was their labor properly compensated and documented?” Moreover, we were left questioning how the context in which we encountered this photo—a standalone image with no description nor label—reproduces silences over these Black laborers, their identities, and their contributions to Williamsburg’s history. Given the blog post referenced above, Colonial Williamsburg has already been asking these questions. Perhaps The Lemon Project can help here, too.

Initially, when I signed up for the internship opportunity provided by Sharpe Scholars, I had anticipated mostly engaging in busy work. However, to my pleasant surprise, my time working alongside Caroline turned out to be thoroughly insightful and an exciting introduction to the roller-coaster that archival work often is. Little did I envision that we would embark on a short but thrilling adventure regarding the mystery photo.

Ultimately, my time at The Lemon Project has been immensely enriching. The identification of the photograph of Black archaeologists at the Governor’s Palace cellar excavation reignited my interest in history and reinforced my willingness to get further involved with the project. I’m delighted to go on new adventures during my next 3 years at W&M and continue to make a difference by researching and sharing long-ignored or forgotten narratives.

1 Comment