By Caroline Watson, Anthropology Graduate Assistant, 2019-present

Database is a bodiless concept, recognizable to many but whose boundaries are difficult to define. Most broadly, our minds and memories are databases that constantly update, however imperfectly, as we see, read, and experience new things. In the scholarly sense, databases are paper or digital places that store key details of a person, object, location, or event. Both of these definitions underscore that databases are sources of information and a central home to multiple types of data that derive from other, diverse sources. Recognizing the form and function of databases is indeed a first step in learning how to think about them critically.

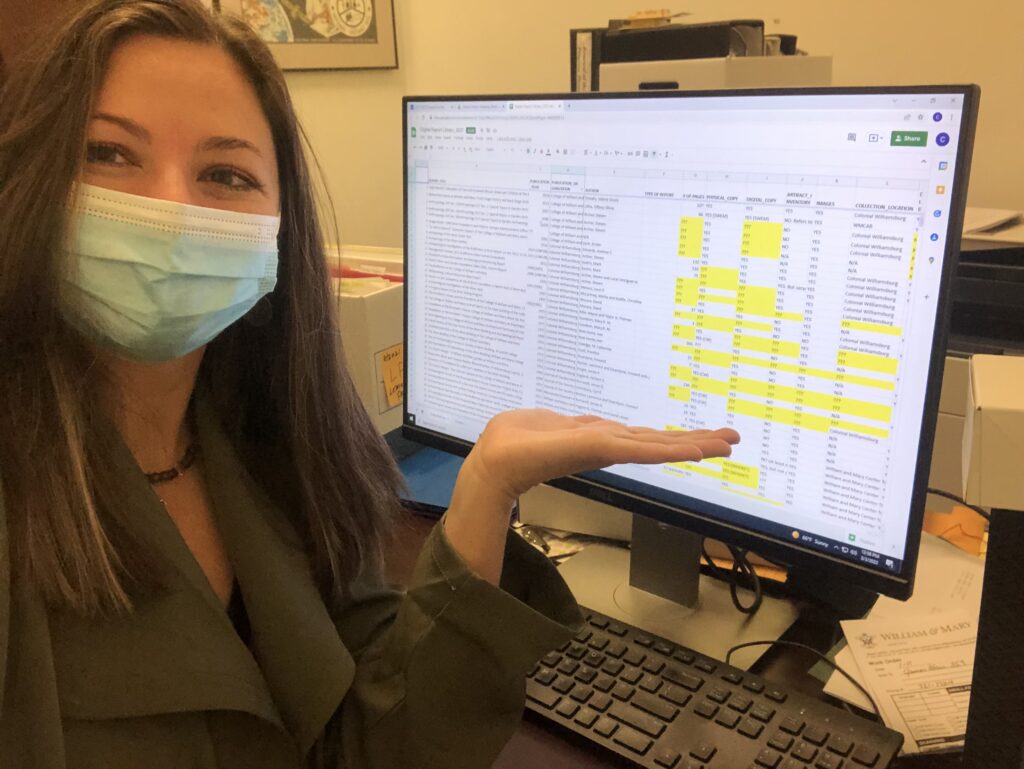

One labor of love The Lemon Project is currently undertaking is the construction of an archaeological database, which I am helping to design as part of my graduate research fellowship. This database will host information relating to the findings from archaeological excavations that have taken place on William & Mary’s campus since the 1930s. In other words, it will be a lengthy and descriptive list of artifacts that have been found on campus. Unfortunately, it is next to impossible to populate this database with every individual artifact that has been unearthed over the past almost century. Norms and regulations surrounding both artifact documentation and preservation of excavation forms have changed over the decades, thankfully now holding archaeologists more accountable for their work. To this end, the task of tracking down the artifact inventories that are dispersed throughout different archaeological companies and organizations has been a challenge in itself and is still ongoing. William & Mary itself houses archaeological and documentary collections that are independent from collections that reside in specific departments, making it all the more complicated to round up and access these data. Once I obtain artifact inventories from archaeological reports, I face the difficulty of standardizing this information into our own database-specific categories. This requires the creation of a standardized system of codes and categories that I will apply to all artifact entries. It is important to recognize the role personal judgment plays here. These codes and categories directly determine the type of information we are extracting from each artifact, and thus the extent of future knowledge about that object. If I decided to label every pottery sherd (not shard!) as simply ceramic, I would miss the crucial distinctions between styles like stoneware, pearlware, and Chinese porcelain, which each have their own temporal and geographic implications. Alternatively, recording every possible detail of an artifact may paralyze the progress of database construction and result in a mass of data that is not necessarily useful to anyone. Navigating this fine line is my current job as someone designing the database. My approach has been to think critically about what details of artifacts are most relevant and can answer the widest variety of research questions, now and in the future. Certainly, The Lemon Project intends for this database to not only spotlight that William & Mary has its own archaeological collections, but also engage future archaeological research projects that highlight the presence of enslaved peoples on campus and focus on the materiality of enslaved life ways and experiences.

Comments closed