By Caroline Watson, Lemon Project Anthropology Graduate Assistant

A common expression in archaeological communities is that theoretical interpretation happens “at the trowel’s edge”[1]. While this expression falls trite on my ears, what it implies is actually quite important for archaeologists, and those conducting research more broadly, to remember. There is no “neutral” moment in archaeological interpretation. Research questions are defined by specific and sometimes exclusive interests. Decisions regarding excavation locations tend to be controlled by the entity funding the work. Materials that come out of the ground are immediately observed and later classified according to object type and perceived function. Finally, where and how archaeological collections are stored also depends on the result of this interpretative process.

In some ways, this process is not purposefully harmful. I’d like to believe most archaeologists do their best to work with reference collections and available published literature to make sure they’re classifying their findings in the most appropriate ways. Nevertheless, artifact classification, especially when approached uncritically, becomes harmful through exclusionary acts. In the case of William & Mary’s archaeological collections, we know a lot about what types of artifacts were used on Historic Campus over the years, but we lack a critical inquiry about who these objects are associated with.

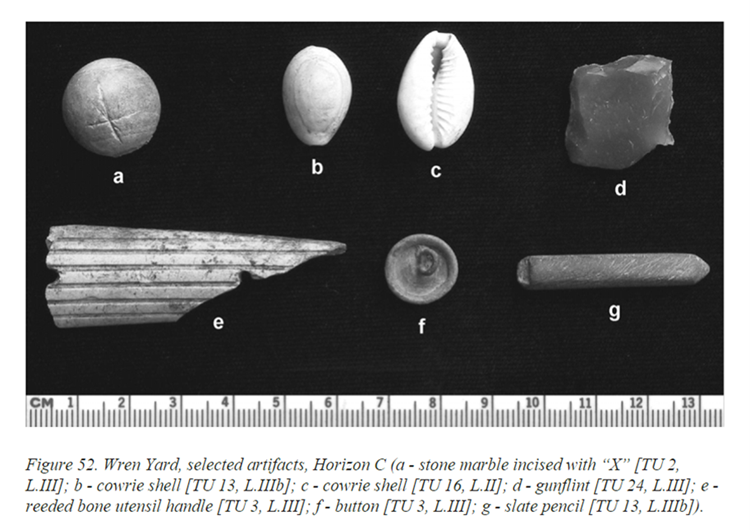

My ongoing documentary analysis of the records and reports relating to archaeology at William & Mary reveals that most archaeological work done on campus has not been guided by the interest to know more about William & Mary’s history with slavery[2]. When archaeological projects at their very core are not designed to question or consider the African and/or African American presence on campus, then how will we ever be able to associate excavated materials with this identity? Archaeologists who assume a “neutral” identity for artifacts until proven otherwise end up, in one way or another, upholding the narrative of campus as an historically and predominately white, elite space. Neutrality is rarely possible. All objects are found within a geographical and sociocultural context. Thus, in a setting like William & Mary, when archaeological findings are taken “as is”, their neutral identity by default is white and colonial. In turn, the artifacts that get flagged as potentially embodying an African or African American identity on campus are the ones we view as being most obviously not white. The marble that was incised with an “X” design found in the north Wren yard has been interpreted as a potential gaming piece used by enslaved people. A cowrie shell, found nearby and within the same stratigraphic level (so, similar time period), may have been a piece of adornment or a medium of exchange for an enslaved person[3]. We value these artifacts for the window, however so small, they provide into the material lives of enslaved people on campus. Yet, what about the tobacco clay pipes, clothing materials, and countless cooking and drinking vessels that have been found on campus in similar locations? We fail to link these materials to non-white identities, which further relegates African Americans on Historic Campus to the “unique” objects and thus margins of William & Mary’s material history. Without a critical examination of our own classification norms, there will never be a broader space for African Americans in William & Mary’s archaeological collections.

I propose we think of William & Mary’s campus and the materials that lie both above and underneath its surface, as an archive. This archive is not a neutral or passive place, but a carefully picked model and the result of several layers of power-laden decisions. Archaeologists working on campus and with campus artifacts hold one form of this power and thus face the certain decision to either uphold campus as a colonial archive or work to expose it. There is much work to be done to get at a more holistic understanding of the material lives of enslaved people at William & Mary. This may require more digging, or maybe it simply requires us to establish a new relationship with the collections we already have. Regardless, perhaps the question we can all start with is, “who are we doing this work for?”.

Image: Screenshot from Higgins III & Underwood 2001: 72, showing incised marble and cowrie shell.

[1] Higgins III, T.F. & J.R. Underwood (2001). Secrets of the Historic Campus: Archaeological Investigations in the Wren Yard at the College of William and Mary, 1999-2000. WMCAR Project No. 99-26. William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research. This is a really extensive report—I suggest checking it out!

[2] This idea was born out of a broader paradigm shift in archaeological theory that sought a more critical examination of the archeologists’ positionality, authority, and role in knowledge verification. If you’re curious about where this all started, see Hodder, Ian (1997) Always momentary, fluid and flexible: towards a reflexive excavation methodology. Antiquity 71: 691-700.

[3] There has been one archaeological excavation that specifically designed its research questions to address the history of slavery on campus. See Monroe, E.J. & D.W. Lewes (2016). Archaeological Assessment of a Site near the Alumni House and the Early College Boundary, College of William and Mary, City of Williamsburg, Virginia. WMCAR Project No. 15-07. William and Mary Center for Archaeological Research.

Very insightful. Thank you for your thoughtful perspective.